by Erica Azim, African Music, Volume 7, No. 4, 1999

In teaching the 1,000-year old Shona mbira tradition of Zimbabwe, I have discovered that Western students have great difficulty in learning to hear mbira music in a Shona way. Though Western students are able to learn to play basic traditional parts, it often takes them years to master the more difficult cross-cultural aspects of the music, including the style of improvisation. Improvising in a Shona way is dependent upon hearing in a Shona way.

Interestingly, even beginning mbira students are often able to experience spiritual states such as peace, clarity and presence, which are among the effects of mbira music that aid its function in traditional ceremonies. These apparently universal effects of Shona mbira music are presently attracting students from around the world to the study of mbira, and hold their interest during the lengthy period required to learn to hear and improvise in a Shona way.

Teaching North American, European and Australian mbira students to hear, play and improvise in a traditional Shona way has been an ongoing challenge, from which I will share some thoughts and experiences here.

How I learned

I began studying Shona karimba, marimba, singing and dance with Dumisani Maraire in 1970, when I was a 16-year old ethnomusicology student at the University of Washington in Seattle, USA. At that time, no recordings of Shona mbira (sometimes called “mbira dzavadzimu” by ethnomusicologists) were available in the U.S. — Paul Berliner’s book and record The Soul of Mbira were yet to be published. After hearing the few scratchy 45 rpm mbira records which Maraire and other Zimbabweans had carried to Seattle, and a few minutes of field recordings made by Professor Robert Garfias, I fell in love with mbira music and decided to be an mbira player.

After two years of study with Maraire, I was privileged to borrow an mbira from Garfias’ office shelf, and started out with only the knowledge of which finger and thumb should play which keys. I taught myself to play by ear, based on my knowledge of Maraire’s marimba and karimba arrangements of mbira pieces, and the few recordings mentioned above. Unfortunately, none of the recordings were solo performances, so I was left to guess which notes were played by the kushaura (leading) and kutsinhira (intertwining) mbira parts. Also, my borrowed mbira was not tuned to the same pitch as the recordings, so playing along with them was not an option. Somehow, I was able to teach myself to play — a lengthy but very joyful process. While my playing was not quite traditional because kushaura and kutsinhira notes were mixed together, the songs were recognizable to Zimbabweans and I became intimately familiar with the location of sounds on my instrument.

After leaving my ethnomusicology studies and working for some time, I was finally able to travel from my native California to Zimbabwe (then Rhodesia) to study mbira in 1974 – 1975. With youthful luck (or, perhaps, the guidance of Shona spirits, as I was firmly told by my mbira teachers), various coincidences enabled me to meet several excellent mbira players within two months of my arrival. This was somewhat amazing, because the racist Rhodesian government placed severe restrictions on me, a young white woman travelling in a country torn by revolution, including a ban on trips to the rural village areas where I had intended to study mbira.

While I learned from dozens of mbira players, my greatest influences as teachers were Beauler Dyoko, Cosmas Magaya, Mondrek Muchena and Ephat Mujuru. I was taught in the traditional way — rote memorization of kushaura and kutsinhira parts to many traditional pieces. However, I was able to learn very quickly, because I had been playing and listening to Shona music for four years, and was very familiar with the instrument. Soon I was performing with my teachers, playing mbira and singing in various traditional and contemporary contexts. I will leave description of my experiences at that time for a future writing. What is relevant to my development as an mbira teacher is the fact that I gradually began to understand much about the system of Shona mbira improvisation and kutsinhira part development, which I wished that I had been taught from the start.

Learning mbira: the Shona and non-Shona student

About ten years ago, I met an American who had encountered mbira for the first time while in Zimbabwe for other studies. He was taught in the traditional way and, being a quick learner, mastered basic kushaura and kutsinhira parts to many pieces. However, if he left the basic parts to attempt even a slight improvisation, his music suddenly sounded completely un-Shona. He could play an mbira piece, but could not hear it in a Shona way and therefore could not improvise in a Shona way

From a Western perspective, Shona mbira music is in some ways musically similar to jazz. “Standards,” in this case traditional pieces, are performed year after year — in the case of mbira, century after century. Each has spacious opportunity for improvisation within the style of the genre. This renders each performance of a piece fresh and new.

Anyone can learn a basic Shona mbira piece through rote memorization, but how is the style of improvisation learned? It has been my observation that improvisation is not taught in Zimbabwe. As the Shona mbira student gradually becomes familiar with the location of sounds on the instrument through learning basic parts to many songs, he starts to add elaboration drawn from his lifetime collection of memories of hearing the piece performed many times by experienced musicians. Selection of specific variations is inspired by what he is hearing in the music at the moment.

When a Shona person learns mbira in Zimbabwe, he or she has heard mbira since before birth — a lifetime. The sounds are already known, and learning to play consists of learning to perform the actions needed to produce the desired music.

How then can the style of Shona mbira improvisation be imparted to a non-Shona student who has no lifetime of musical memories to guide him or her?

Different ways of listening

One significant difference in both structure and listening is that Western music progresses in a linear fashion, while Shona mbira music is completely circular — no note in the cycle is any more the “beginning” or the “end” than any other note. Moreover, performance of the piece may consist of repeating the cycle for two minutes or two hours. The Western mbira student has a tendency, from his linear musical background, to hear the “beginning” of an mbira piece as the point in the cycle where his teacher started when introducing the piece. If his teacher starts at a different point in the cycle at the next lesson, the student may not even recognize the piece as the one he learned! This linear approach must be counteracted in order to learn to listen to mbira in a Shona way.

Another major difference in the Western and Shona approaches to listening is that there is a vertical approach in Western music, with attention to chords and their progression. Shona mbira listening, however, appears to be horizontal, with attention placed on dozens of simultaneous intertwining single note melodies. These are the melodies which are sung and improvised upon on the mbira; without hearing them, the Western student cannot improvise in a Shona way.

Because I started playing and listening to Shona music when I was so young, my “Shona” hearing was unconscious, and I did not realize at first that it would be difficult to impart to my students.

My first teaching methods

My initial teaching method included two principal steps, which I thought of as “how I wish I had been taught.”

The first step was the method I used to learn new mbira pieces myself. I made a compilation of many different recordings of the mbira piece to be taught, performed by various individual mbira players and mbira groups. I instructed students to listen to it all the time — while going to sleep, driving to work, etc. — and to sing or hum along with it. This step was intended to make the sound of the piece familiar, and to compensate for the student not having heard it all her life. By including many different musicians on the tape who improvise in different, but traditionally Shona, ways, a subliminal understanding of the outer limits of Shona improvisation on the piece was also introduced.

The second step was the unmasking of the Shona style of improvisation through teaching the first mbira piece in great depth. First, I taught a very simple basic kushaura part to the mbira piece — the “seed” of the “tree” the piece could become. I gradually taught the student a great variety of ways to improvise on the kushaura part, and then several different styles of kutsinhira parts, in different rhythms. As each variation was introduced, I showed the student how the variation consisted of either doubling or substituting notes from the “seed” part in other octaves. In this way, I illustrated to the student that all the branches and roots of the tree (high- and low-pitched variations) came directly from the original “seed” (basic part).

Other components of my instruction method included teaching the student how to fit kushaura and kutsinhira parts with the hosho (rattle) pattern and each other. This included attention to the subtle shifts of rhythmic feel required to lock the kushaura, kutsinhira and hosho parts into a seamless whole — “one giant mbira.” When requested, I also taught traditional mbira singing.

Learning from teaching experience

Early in my teaching, I discovered that most Western students could only hear the piece they were playing from the point in the cycle where I had started teaching. To counteract this, I introduced the following exercise, to be performed first with the basic kushaura part to the piece, and eventually with all variations and kutsinhira parts:

“Each week, pick a ‘starting point of the week’ and start playing the piece at that point in the cycle every time you play. Sing or hum along with a melody the mbira is playing which starts at that point — it should be easy to sing and should not include all the notes you are playing. Try to find more than one melody starting from that point to sing along with. This singing or humming along is important to keep your listening anchored to the new ‘starting point’ in the cycle. As your hearing shifts to the new perspective, the piece will sound like a completely new piece you have never heard before. You may not be able to play the piece with this new hearing. This is good! Your hearing is beginning to open up. You may have to learn the piece over and over until you can play it while shifting your listening perspective from one point to another. Pursue the exercise until every note in the cycle has been a ‘starting point of the week.'”

After two or three years of teaching mbira, I became very frustrated. Some of my students were becoming excellent mbira players. However, others were putting “correct” variations together in a way that did not sound right to me, and did not sound musical in some way. Why was my teaching method working with some students and not others? What was I failing to teach some of them? I was baffled, and puzzled over this for several months. What is it that lets one know when to use a particular variation, I wondered?

By this time, I had been playing and listening to Shona music more than half my life and could no longer remember what it was like not to hear mbira in a Shona way. An accomplished mbira player does not think about which variation he is going to play next — he immerses himself in the music, listening deeply, and the improvisation just happens. I realized that I enjoy this state so much that I was reluctant to dissect it for purposes of teaching. However, I also couldn’t bear to keep hearing a particularly bright student throw all the variations I had taught him into his playing like an assortment of random numbers –listening to this was excruciating!

I realized that the way I improvise derives from the way I hear a piece during each moment I am playing. I then tried to find out what students heard while playing. I discovered that most students heard only one or two of the numerous intelocking melodies they were playing! What a challenge! How could I teach them to hear more?

I started placing more emphasis on singing the lines the mbira is playing, and developing the selective listening required to pick simple Shona melodies out of the complex interlocking melodies of an mbira piece. Playing mbira is like creating many interwoven threads at once, so I worked with students on hearing one thread at a time, while still playing all of them. We revisited the “starting point of the week” exercise described earlier. I illustrated why a specific variation is appropriate to play when listening to a melody it enhances or extends, but is not appropriate to play when listening to another melody which it disturbs — even when playing the same thing. I encouraged students to listen first, and use variations sparingly — like tasting the soup before adding seasoning (“don’t throw in the whole spice rack, please!”). These efforts at teaching “mbira ear training” have been quite successful, and “mbira ear training” is now a central part of my mbira teaching.

Singing the mbira

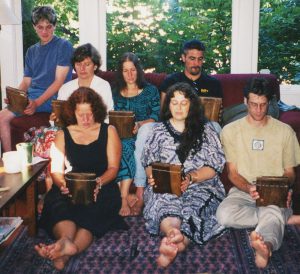

Coincidentally,” mbira ear training” exercises I led at group workshops evolved into a new technique: “singing the mbira.” I led students in singing four to twelve different interlocking melodies exactly as they were being played by my mbira, as I played an mbira part with no variations. When the students could sing their assigned parts correctly, and hear how they related to the other melodies and the hosho pattern, I stopped playing mbira and we continued singing with hosho and clapping. All the notes of the mbira part were being sung by at least one person and we were “singing the mbira!” I then signalled them to add and drop some melodies, so we could hear more precisely the relationship between specific melodic lines within the mbira part. While this style of singing is very closely related to traditional mbira singing, I have never heard this done in Zimbabwe. One Zimbabwean musician told me, “This is something both completely new and completely traditional.”

Pencil-lovers

Western students, particularly those with classical training, have often insisted that they will not remember mbira pieces correctly without notating them. I have responded that mbira is an oral tradition and suggest the compromise of tape recording lessons.

Personally, I believe that notation detracts from the mbira learning experience in three ways. First, it distracts the student from spending her time learning to hear in a Shona way. Second, my experience is that reading notation engages a different part of the brain from that needed to play and experience mbira in a traditionally Shona way. Third, the totality of an mbira piece goes far beyond what can be notated. Notating mbira supports a mistaken notion that what has been notated is the piece. Furthermore, traditional Shona mbira music has been transmitted for a thousand years without notation, so notation cannot be necessary for the mbira student.

Conclusions

After teaching mbira seriously for ten years, I have reached several conclusions. While many Western students can learn to play Shona mbira parts fairly easily, it is very difficult for them to learn to hear mbira in a Shona way, as needed to improvise fluently. However, most non-Shona students can ultimately learn to hear traditional lines and improvise appropriately after spending extensive time on “mbira ear training” exercises and listening to recordings of traditional Zimbabwean musicians.

Changes in “state of being” induced by Shona mbira music, which are experienced by Western students and listeners even before they learn to hear the music in a Shona way, encourage students to begin mbira studies, and to persevere until they master the more challenging cross-cultural aspects of the musical style.