Introduction

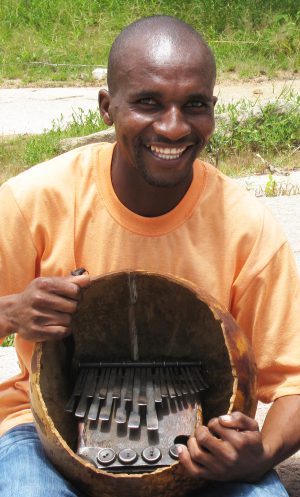

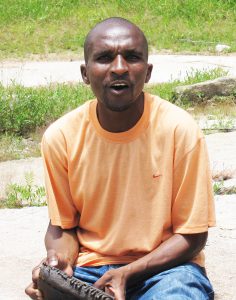

Renold Shonhai grew up as the youngest in a family with 3 older brothers playing mbira – mbira was all around him. At the age of six, Renold was already able to play mbira himself!

Recordings Available From MBIRA

Use the links and listen to samples of Renold Shonhai’s albums.

Biography of Renold Shonhai

(based on a 2009 interview, written by Denver Banda and edited and updated by Erica Azim)

Learning Mbira

“I was fortunate enough to have three older brothers who were good mbira players – Lloyd (late), Clyde (late) and Caution – who grew up playing mbira and attending important ceremonies. Close family relatives like Langton Bapiro and the late Murawo Tembedza were also an influence on the way that I grew to appreciate and understand the music. My upbringing was one where mbira was played on almost a daily basis. There were no two ways about how I was going to turn out, since the music was an important part of the Shonhai household.”

At the age of six, Renold was already able to play the basic kushaura part of Mahororo – he knew the melody of the song first, and learned its name later when his brothers formally taught him. As a boy, Renold had to wait for his older brothers to finish playing and then try to find the melody on the mbira keys while they were resting. They did not want their instruments to get out of tune, but would grudgingly leave Renold to his whims on the mbira because he was the gotwe (youngest child) of the family, therefore he could get away with anything. When his brothers saw that Renold was serious about learning mbira, they taught him to hit each key separately and distinctly, emphasizing the importance of the melody and the strength with which a key must be played. Renold also had a passion for traditional drumming, and learned that as well.

Step by Step

With older brothers who were much more advanced mbira players, Renold was first only asked to play only hosho (rattles) and ngoma (traditional drums) for the family group when they played at ceremonies. In 1995, Renold graduated to playing mbira in the group. Renold had been perfecting his playing skills by watching, listening, and learning from his brothers.

“Caution was staying in Nyamweda and when I was home there, I would partner with him at events we were invited to. When I went to stay in Harare, I would partner with mukoma (big brother) Clyde for he was the one who got invitations to play mbira at dandaros and biras (ceremonies) in the city.”

Renold observes that for him to be well versed in the playing styles of his two brothers, he played the kushaura part for most of the songs that they played and he was told to keep playing that part until he fully understood where the song was headed and how to take it further. Happily for him, because his brothers now lived in two different places, Renold no longer had to play hosho for them, since they each wanted to play with someone who could play the family mbira style. The Shonhai family had two sets of gwarivas (mbira instruments) in different tunings, and they did not want to change the original tunings. When other mbira players changed their tunings to one of the Shonhai tunings, they could all play together. If not, musicians had to take turns on the mbira and the hosho.

Since all the Shonhai brothers were good at mbira, hosho and ngoma, their parents (and later on their widowed mother) were very supportive, particularly because the boys were very traditional, as their father had taught them. Renold clearly remembers the ceremony at which two of the familiy’s four gwarivas (mbiras) made by Steady Shokoni were given to the spirits:

“I was very young at the time and I was on the hosho. I really wanted to also play those instruments (mbiras) that were very important to the family but I was not good enough at the time.”

Mbira Group

Asked how they shared the proceeds from functions they performed at. Renold chuckles and says,

“Unlike other gwenyambiras (mbira players) who got goats and chickens where they played, we always got money and since we would be four or five people working as a unit, the mbira players got more than the hosho and ngoma players. Later this changed because we realized that, since everyone played an important role in helping the mediums get possessed and also to entertain the participants, no one was more important than the other. We decided to share whatever we got equally.”

Shonhai says that when the brothers discussed the issue, they realized that every musician in the ensemble was important. The interdependence amongst the musicians and their collaboration was what made the group good. This was especially true because each of the Shonhais was good at everything that they did during the course of the night, and each of them had had a turn on each of the instruments.

“It was a great observation make that each of us was able to add something to the ceremonies that we attended. We soon knew that everything had to be equal, because if I play ngoma, hosho or mbira to everyone and the spirits’ liking, my shave (talent spirit) for that particular instrument had to be venerated. My shave had to receive what was equal to the effort put in, because it was not me alone playing, but I was simply being used by the shave to show its prowess.”

Songs and Tunings

Renold Shonhai’s favorite song is Nhema musasa, and he loves it especially if it is “well played.” He could not elaborate further on what he meant by “well-played” but the far away look on his face showed his deep attachment to the song. When mbira is played, Renold mainly loves to back the lead singer with mahon’era (low-pitched response singing) and he admits that he is better as a backing vocalist because his brothers were very good singers.

Shonhai enjoys the nyamaropa tuning he grew up listening to. In 1995, while looking for a job, he met mbira musicians playing different tunings such as vembe (also known as mavembe or gandanga), dongonda and other tunings. At first, Renold had trouble understanding how these other tunings were played. But, his passion for the music led him to learn how to play the different tunings and their styles, and he is now confident on any tuning. Shonhai sees nothing bad about the new tunings and ways of playing, but he says his heart is with the nyamaropa tuning. He explains his conviction as follows,

“The nyamaropa tuning mbiras usually move in a pair, and it is their relationship when one mixes the kushaura and kutsinhira parts that one truly understands, and leads to the variations. This is unlike when one plays a dongonda mbira where the whole gwariva’s (mbira’s) upper left manual and the right hand manual are identical and one can take advantage of this fact and just hit a single key on both sides. I love to preserve the nyamaropa tuning because it offers one a chance to listen to two instruments replying to each other.”

Mbira in the World

In school, Renold had problems with people who labeled him as a traditionalist because the family played mbira at home. He was jeered at, but that was not a deterrent because he knew he had the support of his whole family and the spirits. Over the years, he has tried to educate people who look down upon the mbira as an evil and heathen instrument, by using historical facts that the mbira was played for religious purposes and for great Shona spirits like Chaminuka. Shonhai was vehement about safeguarding the history and traditional way of playing mbira, observing that it would be difficult for future generations to understand Shona culture and religion without the mbira and the ceremonies associated with traditional music.

Renold was very frank about places he has played mbira when struggling financially. He played for an upcoming band that mixed mbira and marimba in 2004. He left the group after he saw that, when he played with rural traditional gwenyambiras (professional mbira players), he was losing his way…since some of the notes he was supposed to play, he had become used to hearing from the other instruments in the band.

Rules for Mbira Players

Renold, like his brother Caution, also has rules that he follows with his mbira and its music.

“In the matare (consultations with spirits) we go to as mbira players, we are taught by the spirits not to touch our instruments after having sexual relations with women. This is because this instrument is used for religious purposes and purity of the player is highly valued. If …(not), he will be unclean, for the mbira is for very important spirits.”

Shonhai was particularly emphatic about this, noting that the mbira player is the catalytic agent that facilitates communication between the living and the ancestors.

He went on to share how important it was for him to be pure at all times whenever the mbira is involved, since his brother Caution has a revered family spirit (mudzimu wedzinza). The spirit, of their great-great-great-grandfather VaNzuwa, has favorite songs Muka tiende, Dande and more, and the spirit has a different style of playing these songs. Renold feels that he had an important role in helping to bring the spirit of their great-grandfather. He had this to say about his brother Caution, and how he changes when VaDzuwa possesses him:

“Caution does play great mbira, but when Vasekuru VaNzuwa comes and takes over, the mbira that Caution plays as a medium is far more complex than most of the songs we usually play. On most occasions, the mbira styles that the medium plays are new to me and Caution. When the spirit leaves, I have the task of explaining the different variations that were played and I try to teach Caution what I grasped of them. I have come to notice that over a period of time, the songs that I do not get, Caution will still end up playing when we play long enough. When the spirit is with us, we usually consult him about family problems and this is very helpful for the whole family.”

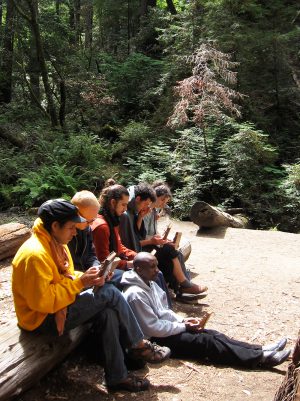

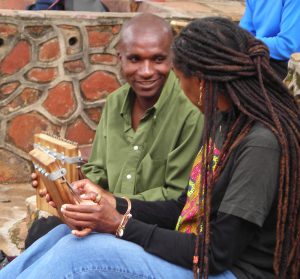

International Tour

MBIRA brought Renold Shonhai to the US in 2010, where his teaching and performances with older brother Caution Shonhai were enjoyed by all.

Life Changes

As of 2018, Renold has been living and working in South Africa many years. He has joined a Christian apostolic group which doesn’t allow traditional mbira, and he no longer participates in traditional Shona ceremonies.

Personal History

Renold Terrance Shonhai of the “Moyo Sinyoro” totem was born on 7 January 1977 at Nyamweda Clinic in Mhondoro, a rural area of Zimbabwe.

Renold Shonhai was born at a time when Zimbabwe’s liberation war was at its peak. Renold jokes, calling himself a child of sevens, since he is the seventh child in the family, born on seventh day of the month in the seventh decade of the century, and he went on to note that some of the defining moments in his life had sevens (for instance the death of his father in 1987).

In 1984, Renold attended pre-school and then primary school at Chimatira Primary School, within close walking distance from his village. The death of his father, Tinaapi Shonhai, in 1987 changed the financial fortunes of the family. Now Renold’s school requirements – fees, books and other educational accessories – were the responsibility of his older brothers. Since the eldest brother in the family was in the army, and the others working for industries in town or market gardening at home in Nyamweda, they could spare a few dollars for him. Renold finished primary school in 1990 and enrolled at Mutukwa High School, about four miles away from home.

High school was a very trying time for Renold, because his older brothers and sisters were getting married and needed to take care of their own families. At this time, the country was going through economic changes that resulted in extensive job layoffs, the end of some benefits for government employees, and the reduction of free stationery and other services in the school system. In this economic climate, it was difficult for Renold’s brothers to support their families along with Renold and their aging sick mother in Nyamweda. Renold managed to pay fees for two terms on his own in 1994.

“I mostly worked in other people’s fields, and with a little savings from playing mbira I managed to pay for school fees and the exam fee. I remember having to write the exam coming from home, without attending school in the last term, because things were very tight for everyone back then.”

After 1994, Renold was not able to go on to Advanced secondary level classes because of his limited financial resources.

“Kumusha (home at the village) there were a lot of very good mbira players and the mbira related functions were few, far between and mainly seasonal. I think it had to do with the area having too many gwenyambiras and too few ceremonies… issues of supply and demand. When there were indeed functions the money was usually too little to do anything really meaningful with it. Often…the times I got to play were at functions like bira and kurova guva ceremonies of members of the extended family, which was…a family duty (unpaid).”

During 1995 and early 1996, Renold helped take care of the family homestead and his mother, since Caution had built his own home, and their other brothers were living and working in Harare. Renold left for the city in mid-1996 to look for employment, with his mother now under the care of one of his brothers’ wives. He spent all of 1997 looking for a job.

In 1998, Renold got a job at ZESA, the national power company, as a contract general hand; he later worked from 2001 to 2003 as a packer of finished clothes; and worked at a food facory from 2004 through January 2008.

Renold married Victoria Mukwisha of the Soko Murehwa totem in late 2001. They have two children, a boy and a girl. Victoria is from Mhondoro and grew up in a family that accepts mbira tradition. She also attends the Roman Catholic Church, which Renold says accepts and is not critical of Shona traditional customs. Renold spent some of his CD royalties from MBIRA to buy a bull, goats, and farming inputs over the years, and some of the money was used for food for his wife and children.

Renold now lives in South Africa.