Introduction

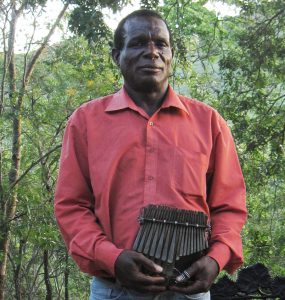

Simboti’s full name is Rinos Kanyerere Mukuwurirwa but most people know him by his totem, ‘Simboti’. Simboti Mukuwurirwa is known internationally for his excellent mbira playing, and his mbira making.

Buy a Simboti Mukuwurirwa mbira on this website. See Simboti at work making mbiras.

Recordings Available From MBIRA

Use the links and listen to samples of Simboti Mukuwurirwa’s albums.

- 3634 Rinos ‘Simboti’ Mukuwurirwa 2019

- 3265 Rinos ‘Simboti’ Mukuwurirwa & Tiri Chiongotere 1999

- 3204 Rinos ‘Simboti’ Mukuwurirwa 1996

Biography

(based on an interview and biography by Denver Banda in 2009, edited by Erica Azim)

Starting to Play Mbira

Simboti’s grandfather Sekuru VaShavashava was a famous hunter, and was the one who played mbira in the family. Rinos’ father Charingeini and other family members did not play at all. Mukuwurirwa’s grandfather moved the family from the Hwedza area and settled in NeDewedzo in the Rusape area, on the eastern side of the Save river near the land of the Maungwe. Simboti says,

“When I started to play mbira, it was my father and his brothers who said that I had taken on what their father was very passionate about.”

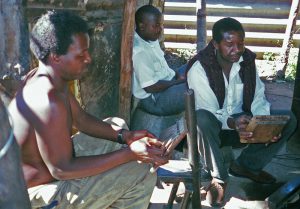

Simboti spent much of his childhood living with his great-uncle Ananias Vakisai Garanewako, in the Mt. Darwin area of northern Zimbabwe. In 1968, at Nyajenje primary school, Mukuwurirwa became friends with Edward Madzinga, and his younger brother Dhundu, who played mbira. Edward and Dhundu’s relatives from the Chihota rural area played a lot of mbira and taught the boys during their school breaks, and provided their first instruments. Seeing his friends playing the mbira, Rinos took an immediate interest in the beautiful music.

“Edward was learning from his uncle Akissi Mudzimire, who was his mother’s brother. The fact that my friend could play was the biggest motivating factor for me to learn to play, and it was added to when I heard mbira players like Farira Nhende, the Rumhaswas, and vekwaNjanja, who frequented Chesa.”

At the home of Rinos’ great-uncle Garanewako, bira ceremonies were held as required by the ancestors. Simboti says it was at these times that he had a burning desire to learn how to play, but initially there was no one to teach him. Garanewako and Rinos’ friend Edward’s father were close friends who helped each other during the ceremonies. Edward began showing Simboti what to do to make a good sound on an mbira. At the same time, Rinos’ cousin Fanuel Garanewako was learning mbira from Farira Nhende, who was the best mbira player in the village at that time.

“I would look at Farira Nhende and Fanuel Garanewako playing Kariga mombe on their mbiras and I paid particular attention at how their fingers moved and the keys that they struck. I would look at, and tried by all means to memorize, the exact keys hit so that I would attempt to reconstruct the patterns later, when I got the chance on the mbira. There was one problem though… Fanuel didn’t want me to touch his mbira and I would go and practice on Edward’s mbira. It was easy for me to get the song. Edward started to teach me Nhema musasa, Taireva, Muzoriwa and other songs that he knew. Edward was a close relative of Mubayiwa Bandambira and it was at his home that I later met that great mbira player.”

Mukuwurirwa recollects the first time he heard about the famous late mbira player Mubayiwa Bandambira.

“We had been playing mbira for the Madzinga clan spirits, and they told us to stop because we were not playing the mbira the way they wanted. When we stopped, they instructed Edward’s father to call Mubayiwa one last time to play, before their homwe (spirit mediums) were dead.”

Mbira Making

During the holidays that began in August 1968, Rinos wanted to buy his own mbira, and he asked for permission from his great-uncle to go and pick cotton on the neighboring farms. This work ensured that he did not have to ask for the money from his great-uncle, who had a huge family. His great uncle consented and Mukuwurirwa spent the next three weeks away from home working. At the beginning of the fourth week he returned home with a little over two Rhodesian pounds, and the first words that greeted Simboti sank his mbira plans.

“Welcome, welcome my great-nephew! You did manage to get a bundle. It’s a good thing you have lightened the burden on me. Since you do not have a school uniform and fees, I will use that money to buy those things that you need so much. Thank you, thank you, Simboti! You do not have to buy mbira when you do not have fees and a uniform, you have done extremely well and helped me out.”

Rinos saw that he could not disagree with his great-uncle, and his plan of getting a new mbira from Farira Nhende at one pound fifty was impossible. Unknown to Simboti, Edward was on his way from Nhende with news that the new mbira was ready. When he arrived, Rinos told him that there was no way he could buy it. That afternoon, Rinos decided to make his own mbira.

“I was sad and needed my own mbira badly. I asked and gained confidence from Edward about making my own mbira. He said that he would loan me his brother’s mbira, and give me advice based on seeing his uncle Akissi Mudzimire make instruments in Chihota. It was from Edward that I got the first instruction about the various materials to use, and how to go about making the mbira.”

In the Chesa area where Simboti and Edward lived, there was a man called Baramba who played njari and had an old broken down truck. They approached him to ask for one of the seats from his ramshackle vehicle. Baramba saw no sense in their enthusiasm for the decrepit seat, and gave them permission to take the junk away. This seat provided sturdy spring wire for making the mbira keys. When Baramba heard that Rinos intended to make an mbira, he asked Simboti to make him one, after Simboti was done making his own. For Rinos, this was a fair trade.

Simboti’s great-uncle was flabbergasted to find his nephew dragging all sorts of garbage into the compound. Rinos didn’t pay attention to his protests, and got himself an anvil. The din he created when he started hitting on the anvil was the last straw, even though Rinos was his great-uncle’s favorite. With a far away look, Simboti recounted events of that early afternoon.

“You do know how quiet and serene the rural areas are, and here I was starting with an axe going Ko Ko ko Ko! and the heavy thud with which the tree fell. After trimming the tree, I got into the compound and started pounding the daylights out of the seat springs we I got from Baramba. My great-uncle could not stand the racket and told me gently but firmly to move to the shade in the fields where the sound was muffled by distance. Secondly, he said that the tree I had cut along the field fence was the last one I would ever cut on his property coz he valued his old trees. I did not protest and moved to the fields.”

Now Simboti learned some of the tricks that he still employs in his mbira making. When the anvil sank into the soft earth it didn’t make a lot of noise, the sound was a dull thud and when Rinos poured water along the fringes of the anvil and the earth, it was barely audible. In later years this ingenious discovery helped him move from the field back into the family compound.

Edward instructed Rinos to make a small furnace to heat the keys, to make them easier to forge, then immediately put them in wet earth after hitting them. This was done to ensure that they remained strong after the rigors of the heat and the pounding. Simboti followed these instructions faithfully. As a 16-year old trying to go to school and finish his mbira, Rinos only worked on the mbira during the weekend. It took him almost two months to complete it. Mbira making was something that he was learning by verbal instruction and he did not know why the keys on Edward and Dhundu’s mbiras had a very dark shade to them. Rinos had trouble tuning the keys and would manage to make a good sounding key and mount it. When mounted it sounded okay but he took it off and returned it into the furnace and overheated it. In doing so he was trying to get the dark color he had seen on Dhundu’s mbira.

“I would take the burned key and remount it to the gwariva but to my surprise, it made a sound that resembled someone hitting a brick wall and not the sweet melody that I would have wanted in the first place. Secondly, when struck, the key did not return to its original position, but stayed flat on the soundboard. I knew that something was terribly wrong, but I could not figure it out. When I told Edward what was happening, he laughed his lungs out and told me not to burn them, that the color I wanted came naturally as the mbira aged, and overheating the keys killed the sound and the strength of the metal. This was one of the most valuable lessons I learned back then!”

Tuning the mbira keys was a problem, but with perseverance Simboti managed to complete the lower left row of keys on his mbira. Next he went on to complete the upper left keys and finally put the nhetete notes on the right side. Simboti states that it got a little easier as he went along, because he was gaining experience through trial and error. He gives credit to his ear, which was instrumental in hearing and making adjustments to the perfect sound he needed for each key. After the painstaking two months, he was able to play a full Kariga mombe, because all the keys were in place and the mbira finished.

“It was around four in the afternoon when I finished my first gwariva (mbira), and I played Kariga mombe on it for a while. After I was content with what I was hearing, I packed my hammer, anvil, files and everything that I was using and went home. When I got there, the whole family was seated outside. My great-uncle took the mbira that I had made and compared it with the one I got from Dhundu and saw that it was the same. He played a few keys on each and heard that they sounded the same. Unsatisfied, he asked me to play Mahororo, and I played. He still doubted my abilities, and asked his son Fanuel to bring his mbira, which I also played. Finally he asked me to put them in a deze (gourd resonator). After playing Fanuel’s mbira in the deze, he instructed me to put mine in. The sound exploded out of the deze, and he was dumbfounded…”How did you make such a good mbira at your age?”…I had no answer for his question, as I was actually surprised about what I had achieved. This is how I started to make mbira.”

The failure to procure his own instrument from Nhende made Simboti strive to make more of his own. When he made his second gwariva, he gave the first one to his friend Edward as tribute to his verbal mbira-making instructions. Mukuwurirwa is forever grateful for the help he got from his friend describing how his relatives in Chihota made instruments. Simboti also attributes his success to his attention to detail as he copied the mbira that was made by a good mbira maker.

In his experience as an mbira maker, Rinos observes the following as matters of fundamental importance: the foundation of the instrument is essential to a good mbira.

“The wood of the gwariva has to be ripe, mature and dry. If the wood is mature and dry enough, you will note that when you mount the keys they would not sink into the wood. If the opposite happens, you have to stop and give the wood time or use better quality wood. I have noted over the years that many mbira makers prefer the moyo (heart), the center of the tree, but I prefer a tree that is dry through and through. I really like working with the mature white wood together with a dull crimson hue because these are the epitome of dry wood from the Mubvamaropa tree. One thing I like about this type is that it very light, unlike the heartwood, and above all it’s very sonorous.”

Mukuwurirwa uses tough spring wire and heavy reinforcing steel to make mbira keys. It baffles the mind how he manages to forge such heavy duty materials. According to Simboti, the metal he uses is very durable and produces the best timbre when one strikes the keys. Getting the desired metal is becoming much harder for Rinos – he used to frequent scrap yards to scavenge for the best, but now his hunting grounds are almost gone. He sometimes has to make do with the commercial steel found at steel shops and hardware spots.

When Mukuwurirwa works with the steel, he first straightens it by putting it into the furnace. He now knows by intuition when it is okay to remove it, to avoid overheating. By alternating forging and putting it into the fire, Simboti tempers the steel, making it harder. When working with spring steel, Rinos hot forges, because cold forging doesn’t work. When he forges, he hits the red hot wire from the edges and slowly flattens it. He says that you can’t hit it cold because you will just expend time and energy without results. The crux of Rinos’ instruments is the wood and steel quality. He says that if one makes instruments with this in mind, they will be as good as possible.

Mbira Playing

“You know when it comes to playing…each and every one of us has his favorite songs, but all mbira songs are wonderful. If one song is not a mbira player’s favorite, it all comes down to the mbira player’s shortcomings in mastering that song and its variations. As mbira players, we should not say that such and such a song is not good just because we cannot play it well. Personally I enjoy most of the songs when I play them. As an example, I enjoy Nyamaropa, Bhuka tiende, Dande, Taireva, Mahororo, and others. If a song is played well and in its entirety, it holds its own amongst others.”

Mukuwurirwa particularly likes the Nyamaropa he learned from Mubayiwa Bandambira. Simboti takes us back to 1972. Famous blind mbira player Mubayiwa Bandambira came with his son Gwengwe to play for the clan spirits of the Madzinga family. Edward came to get Rinos so that he could listen to “real mbira”.

Curiosity got the better of him and he went over to Edward’s and looked at their instruments. They were crude and had a different and beautiful tuning. Simboti noted that the old man’s mbira was very old and the arrangement of the keys was not as orderly as the ones he was used to. The reason for this he later heard was that Bandambira (which means ‘crush mbira’) usually broke his keys and replaced them with crude keys he forged as replacements.

Mukuwurirwa asked Gwengwe to play for him, because he was too embarrassed to ask Bandambira to play. Gwengwe obliged, and played a style of Nhema musasa that Simboti had never heard before. Next he asked for Shumba, and the virtuoso’s son played another variation that Mukuwurirwa did not know. Rinos tried to copy what he had seen and failed dismally. Gwengwe then told him to go and learn from his father, as Rinos was too slow for him to teach.

“I went to the fire where Bandambira was and started playing Nhema musasa with Edward. Later Bandambira commented to Edward’s father that with someone to teach me, I would be a good mbira player. That night was something else. The best Chesa had to offer (Nhende’s group) played first, and later Bandambira and his son took over and opened the ceremony. The sound that I heard there was something new. All the other mbira players refused to play after Bandambira because the threshold he had set was out of our reach. He went on to play for the whole night. That was the last night I played mbira for over a month and a half because I had come to loathe the way I played after hearing Bandambira! I was ashamed of how I played and resolved to learn from him no matter what it took.”

Mukuwurirwa moved to Zimbabwe’s capital city of Harare, still thinking about Bandambira and his music. He knew that the maestro came from Mhondoro Communal Area, but didn’t know the village or the area where he resided. Luck was with Simboti when he met a friend from Mhondoro who came to the Mbare market in Harare every weekend to sell vegetables. Sauti told Rinos that Bandambira was a resident in his village. Sauti went on to introduce Simboti to some of Bandambira’s relatives who stayed in Mbare. The plan was simple, all Rinos had to do was to prepare a substantial amount of money and have a quick ‘hand’ and keen ear. The following weekend he set out with Sauti to meet Bandambira. Simboti used his connection with Edward and Sauti to great effect, because he was treated like a member of the family when he introduced himself. Mukuwurirwa paid $60 to learn mbira, and lessons started immediately.

“Ummm…mudhara uya (that old man) taught me a lot of things from the first time he taught me. He asked me to play all the songs I knew and from them, he said the only one that I was playing fairly well was Taireva. The part he liked was a very basic pattern, and he started to teach me slowly. That weekend I learned three songs, and the fourth one refused to stick. Upon returning to Salisbury (now Harare), I would rush home after work and practice the three songs over a few beers. When the weekend came, I would go back to Mhondoro to learn some more.”

Simboti learned, and played, mbira every weekend. Even when he had vacation from work, he would spend time with the Bandambira family. He began to play with them at ceremonies, though many people did not agree with that, when they heard that Rinos was still learning how to play.

“Bandambira told me that everything that goes on in life is on the mbira. He told me that each and every song has a purpose and a meaning and that people do not just form songs and play them just for the sake of hearing the sound, he said that if you see or hear someone forming a song, then he or she would not be well versed in the mbira, since it has so many ancient songs. He told me that Nyamaropa is the dzinde (root) of the mbira because you do not play it once; there are many ways one can play it. The same goes for other songs like Nhema musasa, Taireva, Bhuka tiende and so many others. There are groups of songs and their variations and one has to know that they should never mix. Each song should have its own style within the varied groups of the same song.”

Learning from Bandambira was a hard task for Simboti.

“When learning pieces from the old man, I failed to see his fingers move, even when he slowed his pace. What we do nowadays was not the way I learned. I was instructed to hit each and every key slowly and in time to the slow tempo. I would go on and on at a dead slow pace and, when he was confident enough that I had got the song, would slowly increase the speed. I learned that learning the right way demanded a lot of patience and concentration. When my ‘hand’ became free, it became easy to learn from him”

Mbira Tunings

Mukuwurirwa has preserved the tuning that Mubayiwa Bandambira used. He had trouble with Gwengwe, who had initially changed the tuning after Bandambira’s death. Simboti restored the tuning through his own mbira, which he had tuned to Bandambira’s, and also from listening to the many recordings that Bandambira made in the late 1960s and 1970s. The name of the tuning is called Saungweme. Gwengwe didn’t see the importance of preserving the tuning. Simboti explained the tuning as follows.

“Saungweme means the sound that a swarm of bees makes when it is on the move. Ungweme is the sweet high buzz that the tuning has. Bandambira told him that the people in the old times always asked the mbira players if they heard the swarm’s sound when they played. It is from the similarity to the sound of the bees that the tuning derives its name. There are two different Saungweme tunings, because there are two different types of bees with two distinctly different sounds. In mbira there are also two different Saungweme sounds. Mubayiwa Bandambira told me that all the mbira tunings came from the insect world. As examples there are Buzabuza and Mazingizi. We should not mistake the western scale as the right thing, because we have our own classification of the tunings.”

Mukuwurirwa contends that the way the mbira sounds was a way people in the olden days copied the way the insects sound. Simboti says this was achieved, because most mbiras hum and buzz like insects.

In learning from Bandambira, Rinos learned that the most important thing for any mbira student is the kushaura part (part that starts first). When one has mastered the kushaura part he can then move on the kutsinhira (intertwining) part. When Simboti played with Bandambira at ceremonies, he noted that the old man always preferred to start with Nyamaropa and its variations. After having played this as the first song, Bandambira had an idea about what the spirit wanted and it took less than ten minutes for the spirits to arrive from the ancestral world.

“I would call Bandambira the mbira player of his time because he had a talent for bringing out spirits and knew their songs. I always try to use all the know-how I gained from him when I play, and it usually works.”

Bandambira died in 1980, before Simboti exhausted the old man’s huge repertoire. Rinos continued to play with Bandambira’s son Gwengwe until disaster struck Gwengwe in 1991 when his right hand was struck by a brick at a beer drinking party, and the injury put an end to his playing.

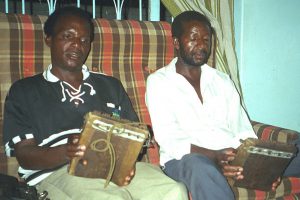

It was a very difficult time for Rinos, as there was no one to match his favorite Bandambira style. Without a playing partner, Simboti now taught his young sahwira (ritual friend) Tirivangani (“Tiri”) Chiongotere how to play…who is his mbira partner to this day.

The Old and the New

“Our mbira culture is slowly being eroded by the new ways of mbira playing that are coming up. I do not condone the way they are doing how they feel as right for them. I think some are doing it out of ignorance, for money and some for the fun that it brings. But, I would love to see the old ways being taught to the young. I would like to use myself as an example…I would love to teach the young ones the same material I learned from Bandambira, and in the same manner he imparted the knowledge to me. He told me the different ways through which the mbira is distorted, and how to guard against this. If we are not careful, the old ways will become extinct and what we would be left with is the material that is awash on the airwaves. It would be very difficult to look for good and original mbira players, if the current trend continues without a move to counter its growing influence.”

Mubayiwa Bandambira’s influence is evident in the way Simboti perceives the clash between modernity/Christianity and traditional culture/mbira.

“I was told that, in the old days, mbira was almost wiped out…that back then, only one person could play in a bira, using a different style. With the churches’ huge influence, mbira took a backseat and was almost shoved out of existence. Bandambira said that in his area there were a few elders of note. Zipembe, Mupondiwa and Chiesa were the ones who fought the tide when everyone was going to church. Our culture is our culture. The church is okay in a number of ways, but it came at the expense of us losing our traditions. Our culture does not forbid us from praying; in the old days our people would pray using the mbira. Chaminuka (a great spirit) had great strength straight from Musikavanhu (the Creator), and for him to do his work he had mbira played for him. The white man came and saw the power of our religion, and tried by all means to sway people towards Western religion and modernity. At church we pray to God, and with mbira it is the same. That is why I had said that everything that happens on earth is on the mbira.”

Simboti give the following songs as examples of how the mbira represents everything we do. Zangaibongo is a song that allegorically speaks of fire, which represents wars, and is also a metaphor for hunger and suffering. Another example is Mandarendare, which means an exchange of fire or blows between two or three, or more, people. He says Nhema musasa is symbolic of a lot of things that people are doing, such as the start of a venture or a journey.

Simboti reiterates that the most important thing on the mbira is the fact that everything that goes on in our lives is found in the songs that are played on the mbira.

“There are songs that speak of trouble, despair and pain. Marenje is a good example, because if you go to hunt in murenje (desert, plural marenje) you will not come home with anything. Machakwi speaks of good times and jubilation. So I say to you, mbira is an instrument that has an education and culture on its own. It teaches us about life, it has the word of Musikavanhu (the Creator) and the religion of Musikavanhu. It is an instrument of restraint to one’s excesses; it governs one’s character to be a better person. Since all we want in this life is on the mbira, we use the mbira to ask Mwari (God) to get what we need. I had trouble when I lost my job at National Breweries, and when I played my mbira, I would cry, playing mbira songs that were related to what I was experiencing.”

Making and playing mbira over the years has supported Simboti’s family. Mukuwurirwa says that he did not heed the jeers of those who laughed at him that he was a professional loafer who played checkers and played mbira. Simboti said that he kept his cool because he knew what he was doing. When he went out play with Bandambira, he learned that pride does not pay. He learned that when it came to playing at people’s ceremonies, he and other mbira players had to do their best without being proud, since he was a vehicle to help the mbira bring out the spirits.

“I learned that you should not be proud and set yourself apart from the rest, just because you have a talent that others do not have. The talent was given to me for a reason and that reason is to help others. I can play for your ceremony, as long as you have transport to go to the place and rusumudzo for my shave spirit (gift/payment to the spirit that enables an mbira player to play well). I cannot turn down an offer to help play for spirits unless there are special circumstances that would force me to do otherwise.”

Mukuwurirwa also loves to hear female mbira players, because he enjoyed listening to them when he played with Bandambira in Mhondoro. He has great respect for female players, noting that it takes a lot of endurance to play for long periods of time.

Simboti has had a number of international students study with him over the years, including several from Japan. He toured Japan in 2019.

Personal History

Simboti was born on 26 September 1952, at the Mukuwurirwa home in the village of Kadungure in the Rusape area, to Miriam NeDewedzo and Charingeini Kanyerere Mukuwurirwa. Rinos’ father was a fisherman with a total of eight children, three from the first wife and five from the second wife.

Simboti’s great-uncle Ananias Vakisai Garanewako took him from his parents when he was a very little boy and lived with him for most of his childhood in the Mt. Darwin area. This was because Garanewako did not have anyone to keep him company, because all his children had grown up. He needed the company of his great-nephew, despite having two wives and a huge family.

In 1962, Rinos began his primary school education in Mt. Darwin at Nyajenje School, and moved on to Chiunye School for his upper primary education. In 1971, Simboti moved to Marymount Mission for high school. In mid-1972, disaster struck – Rinos’ father Charingeini was very ill and wanted to see his son before he died. It had been almost nine years since he last saw his son, and Rinos’ mother went to fetch him. Mt. Darwin was one of the intense sites of the liberation war, and for Rinos to move from there required clearance from the police and the school. This was because many boys his age worked clandestinely as informers for the freedom fighters.

Simboti went back to Rusape with his mother, and failed to continue with his high school education.

“You see it was very difficult to get into high school back then, given the limited number of schools that were available for Africans. I had transferred to Rusape at the worst possible time, because the war was escalating…and, even if I had gotten a place, I could not afford to pay for it.”

Rinos took on adult responsibilities that winter, starting to do small jobs on people’s homesteads and fields. He needed funds to help care for his ailing father, who received a minimum of help from Rinos’ older brothers and sisters, who had left to the cities and marriage. In a cruel twist of fate, on 26 September 1973, Simboti’s 21st birthday, his father died.

“It was a very sobering time, in that I had to work hard to take care of my mother and send my younger siblings to school. I worked for the National Breweries from 1974 to 1982 as a caterer, an electrician and a warehouse clerk.”

From mid-1982, Rinos procured produce from farms close to Harare and sold it at the Mbare market, with the help of a friend who knew the ins and outs of the trade.

From 1986, Simboti settled into mbira making and playing as a way of sustaining himself and his family.

Mukuwurirwa has six children from three marriages. His current wife goes to church and she also loves mbira. Simboti says this is because she knows that mbira is where his income comes from! The money that Rinos has been getting through mbira has greatly improved his livelihood.