Introduction

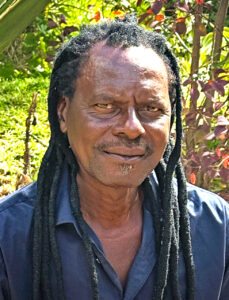

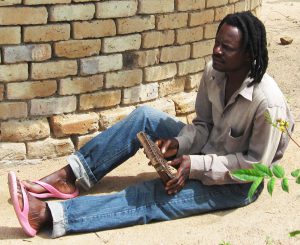

‘Samaita’ Vitalis Wilbert Botsa grew up in a Zimbabwean village family of traditional Shona singers and mbira players, and is one of the most outstanding improvisers within the tradition today. An extremely accomplished mbira player and singer, he creates complex waves of sound seemingly impossible from the two thumbs and one finger used to play mbira. Very traditional in his relationship to the ‘music of the ancestors’, Botsa has performed at important ceremonies throughout Zimbabwe, is featured on 11 albums, and has taught workshops for international students since 2009. “I’m just the car, it’s the spirits doing the driving, making the music,” he says. Samaita wowed audiences and students with his first performances and workshops in the US during 2015; his second US tour in 2020 was cancelled by the pandemic and is now re-scheduled for 2025. He teaches mbira at Chidiya School near his village.

Recordings Available From MBIRA

Use the links and listen to samples of ‘Samaita’ Vitalis Botsa’s albums.

- 3696 Samaita Vitalis Botsa 2024 – Mavembe Tuning Mbira and Vocals

- 3687 Samaita Vitalis Botsa 2022 – Mavembe Tuning Mbira and Vocals

- 3686 ‘Sinyoro’ Caution Shonhai & ‘Samaita’ Vitalis Botsa 2022 Part 2

- 3685 ‘Sinyoro’ Caution Shonhai & ‘Samaita’ Vitalis Botsa 2022 Part 1

- 3648 Samaita Vitalis Botsa & Pasivillias Tandi 2019

- 3627 Samaita Vitalis Botsa Solo 2017

- 3606 Samaita Vitalis Botsa & Erica Azim 2015

- 3600 Samaita & Ambuya Botsa 2014: Vocals! with Mavembe (Gandanga) & Nyamaropa Tuning Mbira

- 3479 Tangai Chinyakare: Shona Songs and Drumming in Murehwa 2010

- 3475 Samaita 2010: Vitalis Botsa on Gandanga/Mavembe Tuning

- 3471 Muzanenhamo Mbira Group 2009

Videos of ‘Samaita’ Vitalis Wilbert Botsa

Biography

(written by Denver Banda based on a 2009 interview, edited and updated by Erica Azim)

Learning to Play Mbira

‘Samaita’ Vitalis Wilbert Botsa was born the youngest child of a very musical village family. Both his father and mother were known as a great singers in traditional bira ceremonies, and his father was the medium of family ancestor spirit VaMushayi. Samaita’s five older brothers all played mbira, and traditional music was part of his everyday life.

During 1977 and 1978, Vitalis began to steal an mbira surreptitiously, to try out the melodies swirling in his head on the instrument. His older siblings did not want anyone to play their instruments, fearing they would get out of tune due to improper handling. Also, their instruments had been officially presented to the family spirits, so could not be played carelessly by children who did not know how to play.

“You see, all my brothers played mbira and they were one of the most versatile mbira playing groups in the Muzanenhamo villages. They received invitations to play at ceremonies and at other important functions. I grew up seeing all my brothers playing mbira and I very much wanted to be like them. If I heard a song that I liked, I would commit the basic melody to mind. When one of my brothers rested or left his mbira, I would then steal the instrument and use it to practice outside.”

Vitalis asked his older brothers teach him mbira, but they refused, so he continued to learn by ear.

“I recall looking for the keys for the basic kushaura (first part) of Muka tiende on my brother’s gwariva (mbira) and the excitement I felt when I hit the right keys. It did not take me long to learn the song, because I loved and was serious about mbira. I did not want to get caught playing mbira without permission, so I had to work fast. I spent the better part of three days battling to get the right keys and to play them as well as my brothers did. By accident they saw me playing something clearly, and they were impressed since none of them had sat down with me for lessons.”

Finally, gradually, Vitalis’ older brothers let him play mbira with them at ceremonies. First he played hosho (rattles), but later he began to play both kushaura and kutsinhira mbira parts in the family group. As the youngest member of the group, he did not get a fair share of the proceeds from the ceremonies they attended — this was a thorn in his side for a long time.

“I would tell them that I also had a shave (talent spirit) and it was fair to venerate my shave by sharing everything equally, since we were all brothers. They would brush me aside and dismiss my demands as the ranting of a schoolboy. My brother Markios made mbira instruments, but he didn’t listen when I told him that I wanted an mbira of my own. It was much later when I was working that I managed to save enough to buy a gwariva (mbira).”

Playing Mbira as an Adult

Of the kushaura and kutsinhira mbira parts, Samaita prefers to play kushaura. He contends that if one knows the high lines well, and many styles to employ when playing kushaura, one can change the feel, texture and pace of a song.

Mid-1990, Botsa met Forward Kwenda in Mbare, Harare, at the house of traditional healer VaGushungo, and Kwenda became his main mbira partner for some time.

Samaita says that Kwenda influenced how he listened to, understood, played, and studied mbira, and that they were very thorough in the way they approached mbira music. It was no longer a matter of just playing, but of having the instrument tell you where the song was going and following what it dictated. During the time they played together, he gained a deeper understanding of how the two parts can interact.

“The mbira that I played with Mhofu (Kwenda) spoke a language of its own and all we had to do was listen, and listen some more. We could go to the bush with our gwarivas (mbiras) and bute (sacred snuff) and play all day with no concept of time. ”

“Playing with Mhofu was a rewarding and challenging experience especially when he got possessed in the middle of a song. At first I had difficulty understanding the virtuosity of his spirit’s pieces, but over time I learned how to play well with him, because I had learned how to listen deeply.”

Botsa and Kwenda were in high demand, playing for spirit mediums throughout the country, including important places such as Dzivaguru and Nyandoro. Unlike the unequal situation he faced when playing with his brothers, Botsa and Kwenda shared whatever they received equally. The mavembe, or gandanga, tuning that Samaita played with Kwenda was very popular; while his family played only nyamaropa tuning. Botsa says that the tuning amazed him, and that he prefers it to nyamaropa tuning, though enjoying both.

“Many gwenyambiras play nyamaropa tuning but it takes a great mbira player to play mavembe tuning well. That is my thought but I am not saying nyamaropa is bad because, whenever we went to play, we would start off the ceremony with nyamaropa tuning. When we reached the wee hours of the morning, we would change and play mavembe tuning because we felt it was the time that people really wanted to listen to deep mbira.”

Botsa also began to sing seriously during the 1990’s. Through huro and kudeketera singing styles accompanying the mbira, he talks to, prays to, consults, and venerates his spirits and forefathers.

In 2009, Botsa named Nhema musasa as his favorite song, that he especially enjoys on nyamaropa tuning with a good kutsinhira player backing his wild variations. On mavembe tuning, his favorite is Marenje, the first song he learned on the tuning, and he plays so many different styles of it!

Botsa is a strong advocate for the preservation of the ancient songs, and old ways of learning and playing mbira.

“I feel that mbira should not be mixed with other instruments, because the music loses its authenticity and purpose if we do that. The contemporary styles of mbira where you find five mbiras of different voices (tunings) collaborating to form a song is honestly a commercial ploy to make money. My personal opinion is that I don’t like it and I don’t want to learn it, because I haven’t even exhausted the traditional ways of playing. To fix this problem, we need to have more airplay of the old style mbira…so much that everyone can hear and understand the difference.”

For Botsa, the most important thing about the mbira is its depth and power to call spirits. He has remained steadfast in his tradition, even after negative criticism from those with other religious beliefs. He says that mbira has helped him both financially, psychologically and spiritually for more than 45 years, and that will not stop.

For six years, Botsa played with nephew Campion Botsa and Lovemore Mutandwa in the Muzanenhamo Mbira Group. Currently, he spends a lot of time playing solo mbira and developing his solo playing, plays occasionally Musekiwa Chingodza, as well as enjoying playing with Erica Azim whenever they are in the same country. His mother, Ambuya Christine Botsa, used to add fabulous vocals when Samaita played mbira, as heard on their 2014 album when she was 90.

Samaita toured California and Oregon, USA with Erica Azim in 2015, to overwhelming acclaim. He has been teaching mbira at Chidiya school near his village since 2015.

Personal History

Vitalis Wilbert Botsa of the “Mbizi yekwaMutasa/Samaita” totem was born in Muzanenhamo-Gavaza, Murehwa Communal Area, Zimbabwe, on 20 October 1963 to Merekiyo Tangai Botsa and Christine Majecha Chipere Botsa. He was the youngest child in a family of nine children – six boys and three girls.

From 1971 to 1977, Vitalis attended the local Chidiya Primary School. But, the intensity of the liberation war led to the closure of many schools in the area, including his. After majority rule in 1980, Vitalis returned to school, and attended high school until 1986.

From 1987 through 1990, Botsa lived in Harare working for a detergent manufacturer, then as a security guard, then as a builder. During the 1990’s he gradually became a successful ‘market gardener’ in his village, specializing in fresh vegetables that he grows with his wife and children. He uses public transportation to transport his produce from the village to markets in Harare and Marondera, where it is popular. He has used the royalties from his internationally popular mbira albums to buy a water pump and fertilizer, expanding his farming.

Botsa is happily married to his high school sweetheart, Regina Muchenje Botsa, and they have five children.